Viruses are incredibly abundant; in fact, there are an estimated ten nonillion (10 to the power of 31) viruses on earth. Only a fraction of them have been known to infect humans, but new viruses are constantly emerging. Many well-known infectious diseases are caused by viruses, including the flu, chickenpox, herpes and COVID-19.

A weakened immune system can lead to an increased risk of infection and some other diseases. There are, however, several things that can help support immune function and promote healthy ageing.

What is a virus?

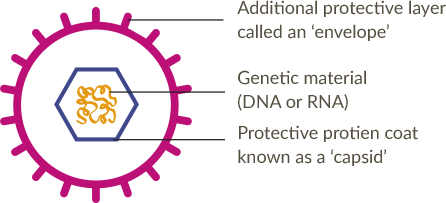

Viruses are submicroscopic pathogens (germs that are too small to be seen under a standard microscope) that can enter the body and cause illness. While there are several different types of viruses, the most basic ones are made up of only two or three parts (see diagram). Regardless of type, all viruses have one thing in common: their extremely simple structure makes them incapable of thriving on their own. They need to be inside a living organism (such as a human, animal or plant) to reproduce and cause disease.

How does a virus make us sick?

If a virus successfully enters a host (i.e., the human body) and infects a cell, it can reprogram (or 'hijack') the cell's machinery to produce copies of itself, disrupting the normal function of the cell.It’s through disrupting the function of or killing cells in our body that viruses can make us sick. Disease symptoms can occur as a direct result of this cellular damage, but more often due to inflammation caused by the body’s immune response. Fever, pain, and a general feeling of being unwell are all common symptoms that occur when the immune system recognises the signs of infection and tries to fight back.

Unfortunately, some viruses have evolved strategies that help them hide from the host's immune system, which can make it difficult for the body to clear the infection and potentially lead to chronic disease or complications.

How is a virus transmitted from person to person?

For a virus to cause disease, it must first enter the body of its host and infect a cell. We can pick up viruses via direct and indirect contact:

Direct contact (including droplet spread)

Can occur when someone shares close physical contact, such as kissing or sexual intercourse, with an infected person; or when spray from an infected person (e.g., from a sneeze or cough) is transferred to another person before falling to the ground.

Indirect contact

May occur after touching a contaminated surface (e.g., a handkerchief, handrail, doornob, or contaminated needle), inhaling airborne particles, eating contaminated food, or through a bite from an infected animal or insect.

It’s important to note that it’s possible to get infected with a virus even when there are no signs that someone around you is sick. A person can have a viral infection despite being asymptomatic (not showing any signs or symptoms of an illness). An asymptomatic person may still be contagious, meaning they can still spread the virus to others. Many viruses can also survive on surfaces outside of the body for extended periods of time.

Some ways to help prevent viral transmission:

- Follow good hygiene practices. This includes regular hand washing with soap and water for at least 20 seconds (or using an alcohol-based hand rub if no water is available), and covering your mouth and nose—with a tissue (throwing it into the rubbish after using), or with your upper elbow or sleeve—when coughing or sneezing.

- Avoid touching your face, particularly your eyes, nose and mouth (as this is how viruses and other germs can spread).

- Maintain physical distance from others in crowded places.

- Stay at home when sick to limit contact with others as much as possible and reduce the risk of infecting them.

- Avoid close contact with people who are sick.

- Regularly disinfect and clean objects and surfaces that may be contaminated.

Disclaimer

The above information is not intended to substitute for professional medical advice and should not be relied on as health or personal advice.

NP-AU-NA-WCNT-210009 Date of GSK Approval: June 2021